“In Memory of Tomorrow”: Impressions and Overview of the Works of Participating Artists Mohamed Harb, Aref Masalha and Munther Jawabreh

Ahlam Shibli

The A.M. Qattan Foundation brought us together through the photography project, In Memory of Tomorrow. The project was planned and organised by Dr. Yazid Anani and coordinated by Mr. Johnny Kort. I see this as a truly inspiring experience, which gave me the opportunity to follow the journey of these distinctive artists and understand their concerns and ways of thinking. I found their artistic practices quite enriching, leaving me full of innovation after studying their approaches to both the COVID-19 pandemic and the ever-growing ‘endemic’ of the occupation. Learning about the strong intuitions of the artists and the ingenious ways they linked together these complementary problems allowed me to comprehend their visions. This also familiarised me with the creative ways they may deal with this reality and their complicated life conditions.

The Foundation’s project, which made this exchange possible, allowed us all to benefit. I had a very positive interaction with the Foundation and found their approach and methodology to be quite helpful. This experience enabled me to see things more meditatively and patiently to gain better insight and progress more effectively.

In his project, Mohamed Harb moves us between public and private spaces. His camera roams the streets of Gaza in search of footage that depicts the daily lives of local market vendors. He then documents his family within the private sphere and activities within school. The commonality that links these three spaces is the crises they are both under: namely the COVID-19 pandemic and the Israeli occupation. Regarding COVID-19, at this stage, mask-wearing by non-medical staff is the only evidence of the pandemic, a particular action in current times. Therefore, empty spaces are typical in the Gaza Strip, which suffers from the Israeli occupation’s daily violations of human dignity and collective quarantining.

Mohamed Harb highlights the great similarity between the COVID-19 pandemic and the Israeli occupation in terms of their detrimental effects on people’s private spaces. Harb was accustomed to suffering under occupation since his childhood days. Through his family’s symbolic scenes, the artist shares his feelings and highlights Gaza’s current situation. He also allows us to enter his household and meet his family members, his children moving back and forth between art, creativity and the ‘cage’ (the COVID-19 masks remain stuck in that metamorphic cage). The artist portrays his mother’s stillness as she reads the Qur’an while wearing a mask: Perhaps this symbolises Palestine’s fate under COVID-19 and the Israeli occupation, while relying on a divine power to strengthen its patience. School, the third space, is like a mother embracing her children who want to be liberated but submit to the current circumstances.

Aref Masalha chooses as his media analogous photography and black-and-while film. This is not done as a work strategy but, rather, to satisfy his passion for using these media and delve into the “undulating” details between the black and white shades. What catches our attention in these pictures is the intrinsic relationship between devices and people and the relation between clocks and time. For example, his photos often indicate the time and the state of waiting. Devices, clocks, oxygen and flowers are all symbols of the passage of time before the end. This can symbolise the Palestinian situation in Jerusalem, which suffocated under the Israeli agencies that determine the continuity and extent of its life. The Palestinian body became impotent, restricted and immobile (so to speak), while relying upon Israeli agencies to continue to breathe. In his photographs, Masalha captures death just before its occurrence and highlights the illusion of ‘healing’ from the occupation, whereas he sees death around the corner. Most of the pictures were taken inside hospital rooms, where names are simply replaced with signs, communication is prohibited and loneliness and suffocation become the symptoms of estrangement—similar to a slow and inevitable death. Death itself comes along with the questioning of its occurrence; there are suitcases hanging on the wall and waiting for their owners. (In the Palestinian context, suitcases refer to displacement, deportation and exclusion).

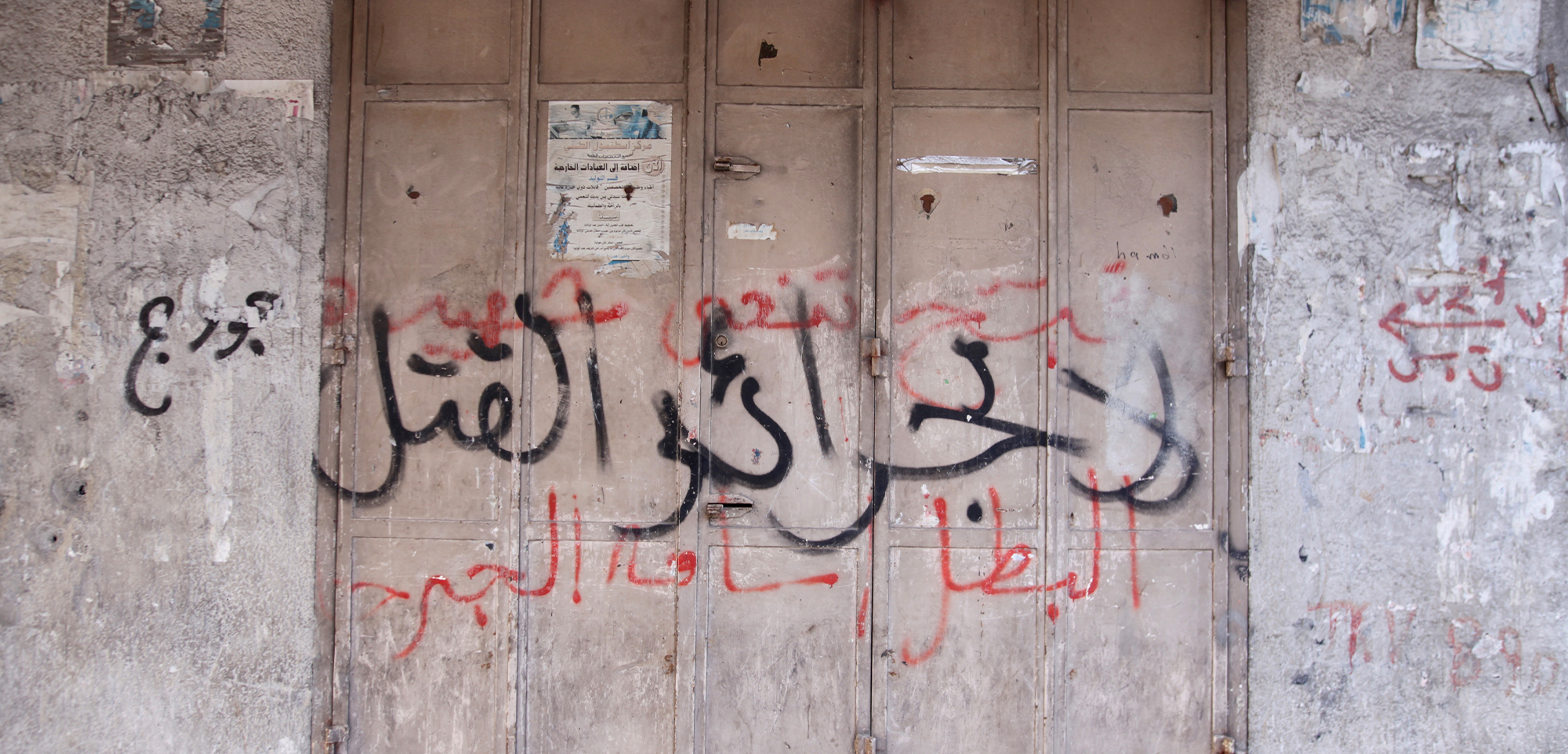

Munther Jawabreh introduced us to an unknown person: their face cannot be seen and identity cannot be known. This symbolic person can be the prison warden, inspector, ruler or oppressor and at the same time a healer, guard, protector or saviour. Only the colours change in this respect. This person can be Palestinian or Israeli. For example, the inspector at the crossing point towards Bethlehem can be an Israeli or Palestinian security guard, both of whom perform a similar function of blocking roads (as seen in the recurring image). In this context, the coronavirus is portrayed as security personnel preventing people’s passage and able to wound, hurt or even kill, the wire strips used as an apt metaphor. This likens the COVID-19 pandemic to Palestinian suffering under the Palestinian Authority and Israeli occupation, as both confine movement and prevent a free and dignified life. There is also a confusing symbolism when Jawabreh transforms another anonymous person in black into white. Perhaps this person, whose feet are shackled with stones, is the saviour who carries with him a delicately fragranced jasmine flower that can blossom if given a bit of water and a little hope. This might be the paradox within this person, especially because the stones are within reach.